Digital Zoom vs. Optical Zoom

What is the difference between digital zoom and optical zoom? This is a question that some users ask; while all experts agree that optical zoom is much better and more effective, some may have a hard time explaining why.

Imaging systems (whether thermal, visual, or other spectral types) provide visual information on distant targets beyond what the eye can see. To gather enough information for tasks such as detection, recognition, and identification, the imager must provide an appropriate field-of-view (FoV) to allow significant magnification so that the user can see the necessary details. To increase magnification (make the image appear larger), the field-of-view must be decreased. Here’s where some confusion begins to take place.

Optical Zoom

Optical zoom systems move the optical elements to change the focal length of the imaging system. A longer focal length means more magnification, which equates to the ability to image a target at a greater range. Optical zoom systems can be either stepped zoom (where there are fixed, discrete zoom levels) or continuous zoom, in which the focal length can be continuously adjusted to whatever setting the user wants. Stepped zoom systems are simpler from an optical design standpoint; some years ago, these were common in the thermal imaging world. Continuous zoom designs have been the standard in visual imaging for many years and became much more common in thermal imaging around 2010. Today, nearly all variable focal length thermal imaging systems use continuous zoom capabilities.

A key attribute of an optical zoom system is that the image created by the optics utilizes the entire sensor array, regardless of the zoom setting. This means that the optical resolution (the ability of the system to discern small details) increases as the FoV narrows. This is where the optical zoom system differs from digital zoom.

Digital Zoom

In a digital zoom system, the pixels in a section (usually the center) of an image are expanded, while the optics maintain the same focal length. The pixels in the expanded area are simply replicated and then smoothed using advanced image processing algorithms. This zoomed-in area appears larger on the screen, but the effective array is smaller. The new image uses only a subset of the pixels from the original image, meaning the digitally zoomed image contains less information than the original image. This contrasts sharply with an optically zoomed image, which uses all available pixels to form a more detailed image.

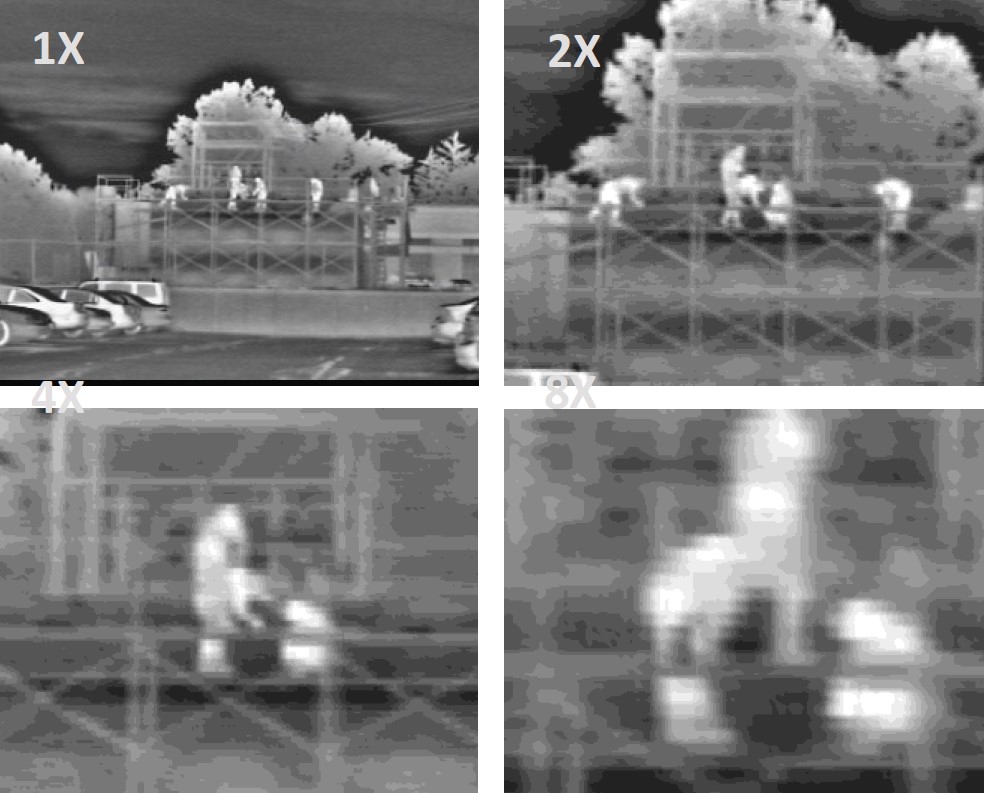

As you can see in Figure 1, the image shows less detail as the zoom level increases. At high zoom levels, the image becomes pixelated because the system is trying to form an image with less information (i.e., fewer pixels being expanded).

Although these effects always occur with digital zoom, not all digital zoom algorithms are the same. In Figure 1, notice that the zoom levels (1X, 2X, 4X, and 8X) are all powers of 2. This is because decreasing the image size is computationally easier when done by powers of 2. The algorithm used to smooth the image is called bi-linear smoothing, where simple averaging of surrounding pixels is used. Stepped digital zoom (by powers of 2) and bi-linear smoothing are simple algorithms that can be performed on low-power processors, which is why they are common in many thermal imagers. The noticeably lower quality (beyond 4X) is why most digital zoom systems don’t go beyond 4X, or sometimes even beyond 2X.

With all of this in mind, is there any use for digital zoom? The answer is yes, but only in limited circumstances. One such situation is when viewing an image on a very small monitor. If the monitor (or portion of a monitor, in the case of a windowed screen) uses less pixels than the actual image, then the user can digitally zoom up to that point with little to no loss of resolution. While this is not frequently the case, it can happen. When it does, the quality of the digital zoom can make a significant difference.

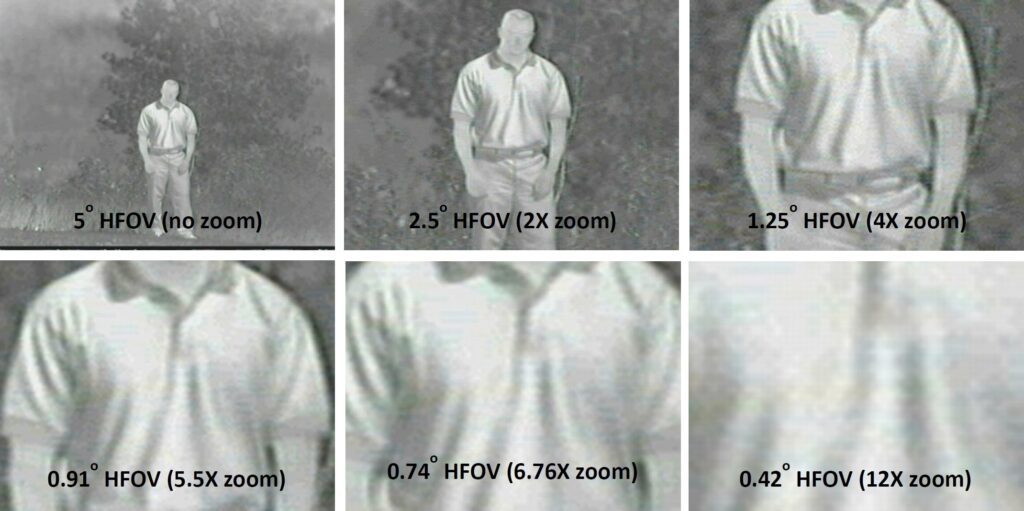

Higher quality continuous digital zoom (sometimes called fractional zoom) can be performed, but it requires more powerful on-board imager processors. This allows the user to digitally zoom to any arbitrary level, not just levels that are powers of 2. IEC Infrared Systems utilizes continuous digital zoom paired with a more sophisticated type of smoothing called the Lanczos algorithm. This method produces a much smoother digital zoom and even allows it to be usable at higher digital zoom levels, as shown in Figure 2. Note that, even up to 12X level, the general quality is preserved to a greater extent than at 8X using the bi-linear method.

Summary

To summarize, optical zoom is superior to digital zoom because optical zoom uses all the pixels in the imaging array, not just a subset. This preserves the imaging system’s resolving capabilities, even in the narrower FoV. Digital zoom, on the other hand, discards information from the image because it simply magnifies a subset of pixels and discards the rest. Digital zoom can have some use in limited cases, such as when the viewing window is very small. Despite its limitations, digital zoom remains popular among many users. For small viewing areas and for general user interest, the more sophisticated continuous zoom with Lanczos smoothing, as performed by IEC imagers, provides a better, more usable digitally zoomed image.